cupoftea

Advanced Member level 6

Hi

We are doing a fog detector for motorways.

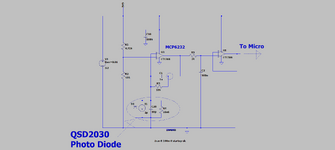

LTspice and PNG schem attached.

We simply use a QSD2030 Photo diode to receive light from a nearby Infra-red LED.

It has peak sensitivity in the Infra red region so is ideal since it means

ambient light wont cause so much reading inaccuracy.

Photo diode.

If fog gets between the LED and photo diode then the photo diode current reduces and the output

voltage of the opamp reduces. So obviously there's no need to respond to fog in

a millisecond, so we choose a 1nF feedback capacitor as shown.

Also a 1MEG feedback resistor. These give a Bandwidth of 159Hz which is plenty for this.

I mean, we will take 5 readings at 1Hz sample rate, then average those for the one reading.

We will filter the infra red light to the photo diode such that in brightest sunny days, only 2uA flows in the photo diode.

Then we have good "full scale deflection". The opamp Rail is 3v3 and we bias its Non-Inv with 0.58V as shown.

The following shows our method...

We hired a consultancy to do this for us but they came up with an AC coupled solution with a 10meg feedback resistor and 0.58v bias.

This would have meant a maximum of 272nA of photo diode current which is likely the dark current at 85degC or something!

(they used a 2p2 feedback cap). Anyway, they also AC coupled the output of the "photo diode opamp" (obviously with a MLCC capacitor) to the follow-on

stage which was an AC coupled non inverting opamp stage (capacitor in series with its input resistor to ground).

Also, they then AC coupled the output of that non inverting opamp to an RC filter, and then fed that to the microcontroller.

Dont see why they bothered with the AC coupling. Also, dont see why they needed the non inverting stage after the opamp

that they used with the photo diode?...they would already have been near the 3V3 rail without needing further amplification.

We are doing a fog detector for motorways.

LTspice and PNG schem attached.

We simply use a QSD2030 Photo diode to receive light from a nearby Infra-red LED.

It has peak sensitivity in the Infra red region so is ideal since it means

ambient light wont cause so much reading inaccuracy.

Photo diode.

If fog gets between the LED and photo diode then the photo diode current reduces and the output

voltage of the opamp reduces. So obviously there's no need to respond to fog in

a millisecond, so we choose a 1nF feedback capacitor as shown.

Also a 1MEG feedback resistor. These give a Bandwidth of 159Hz which is plenty for this.

I mean, we will take 5 readings at 1Hz sample rate, then average those for the one reading.

We will filter the infra red light to the photo diode such that in brightest sunny days, only 2uA flows in the photo diode.

Then we have good "full scale deflection". The opamp Rail is 3v3 and we bias its Non-Inv with 0.58V as shown.

The following shows our method...

We hired a consultancy to do this for us but they came up with an AC coupled solution with a 10meg feedback resistor and 0.58v bias.

This would have meant a maximum of 272nA of photo diode current which is likely the dark current at 85degC or something!

(they used a 2p2 feedback cap). Anyway, they also AC coupled the output of the "photo diode opamp" (obviously with a MLCC capacitor) to the follow-on

stage which was an AC coupled non inverting opamp stage (capacitor in series with its input resistor to ground).

Also, they then AC coupled the output of that non inverting opamp to an RC filter, and then fed that to the microcontroller.

Dont see why they bothered with the AC coupling. Also, dont see why they needed the non inverting stage after the opamp

that they used with the photo diode?...they would already have been near the 3V3 rail without needing further amplification.